Painting © 2004 Loz

Arkle

Website

© Copyright 2000-2011 Alan White - All

Rights Reserved

Site optimised for Microsoft Internet Explorer

"This Cat's Got the Yellow Dog Blues"

- origins of the term Yellow Dog by Max Haymes

Railroads

have always been an integral part of the blues; not only in inspiring the boogie

rhythms of countless rural guitarists, barrelhouse pianists and harp blowers,

but also the lyric content of the blues singer. The earliest blues that has been

noted featured one of the most famous railroads; Mississippi’s “Yellow

Dog”. In this article I shall be not only seeking out the origin of the term

but I will also attempt to identify the railroad it refers to.

The blues in

question is the song that W. C. Handy was to “compose” later as “The

yellow Dog Blues”. In 1903 Handy has related how he heard a lean, raggedy,

black guitarist in Tutwiler’s railroad depot, singing of going to where the

‘Southern cross the Yellow Dog”. Writers have speculated the origin of this

nickname for over five decades. The picture becomes even less clear as at least

two railroads seem to be involved; the Yazoo & Mississippi Valley (Y.&M.V.)

and the Yazoo Delta (Y.D.)

The

“Southern” was the Southern Railway which “began operations in

1894,”(I). This dates the line “where the Southern cross the Dog” back to

1894 at the earliest. Cohen tells us “The Dog” was the Yellow Dog, a

vernacular name for the Yazoo Delta Railroad.”(2). “Dog” or short-dog was

railroad slang for a local or branch line. Cohen refers to Handy’s anecdote as

to how this railroad acquired the name. This involved the black trackside worker

who, when asked, looks up at the locomotive nearby and replies rather

uncertainly, that the letters “Y.D.” on the tender, stand for “Yaller Dawg,

I guess”. But no explanation was given as to the reason why.

Cohen says “The Yazoo Delta lasted for such a brief period that we can date the verse’s origin to within a couple of years. Opened in August, 1897, the Yazoo Delta first consisted of 20.5 miles of track between Moorhead and Ruelville (sic), to the north. By 1899 it had been extended in both directions – 21.5 miles to the north to Tutwiler, and 15 miles to the south to Lake Dawson. By 1903 the company was no longer in existence, having been acquired by the Yazoo and Mississippi Valley Railroad, a subsidiary of the Illinois Central Railroad. Possibly the name Yellow Dog was later applied to the Y&M.V. line.”(3). The Yazoo Delta R.R, was so short-lived that it is not mentioned in three different histories of Yazoo County or by most blues authorities when discussing the Yellow Dog. Although Paul Oliver refers to a shortened term for the line as “Yazoo Delta”(4), he is still referring to the Y&M.V. The Y.D. itself makes a brief appearance in James Cobb’s excellent “The Southernmost South” (1992). But otherwise silence reigns regarding the Yazoo Delta R.R.

Fig.

1 Y.&M.V.R.R. train station at Yazoo City, prior to 1900

On the other

hand, the first train steamed into Yazoo City railroad station on the Y.&M.V.

in 1884, some 13 years before the Y.D. came into existence. J. B. Wilson

reported at the time with obvious civic pride “this year witnessed the

completion of the Yazoo and Mississippi Valley Railroad, running from Jackson,

Miss., to Yazoo, Miss., (sic), the county seat of Yazoo...This has been built as

a feeder to the Illinois Central R.R.” (5). He adds “The Y&M.V.R.R.

connects us with the outside world at Jackson, Miss.,”(6).

But the real

clincher for the Y.&M.V. as the rightful

heir to the title “The Yellow Dog”, was the creation of the settlement of

Moorhead. When Handy heard the now-famous refrain at Tutwiler, the “ragged

Negro” was singing about “going to Moorhead, Miss., where the Southern

Railroad crossed the Yazoo and Mississippi Valley, called “Yellow Dog” by

blacks and whites.”(7). Handy gives the explanation of his 1903 guitarist:

“At Moorhead the eastbound and the westbound met and crossed the north and

southbound trains four times a day. “(8). A fairly busy railroad junction it

seems, in 1903. Over 30 years later Big Bill (Broonzy) would

declare:

“The

Southern cross the Dog at Moorhead,

an’ she keeps on through,

The Southern cross the Dog at Moorhead, an’ she keeps on through.

If my babe gone to Georgia, believe I’m goin’ to Georgia too.”(9)

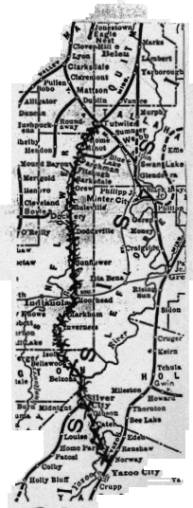

Fig.

2 The famous railroad crossing at Moorhead

Unlike

Cohen, it is quite clear to me that Big Bill is referring to the Y.&M.V.

crossing the Southern, rather than the elusive Yazoo Delta R.R.

About a year

after the historic (for Yazoo City) arrival of the Y.&M.V. one Chester H.

Pond founded Moorhead, “Pond enlisted financial support in building a railroad

to service the rich lands north and south of Moorhead which resulted in some

twenty miles of track being laid. Then a chain of flat-cars pulled by a

second-hand locomotive soon earned the name of the “Yellow Dog”. (10). By

Cohen’s own admission this railroad, c.1835, could not have been the Yazoo

Delta R.R., still some twelve years in the future, so it must have been part of

the Y.&M.V. Perhaps initially, Pond leased his section of the Yellow Dog

from the Y.&M.V. or acquired running rights for his trains. Either way, this

line was so successful that the Illinois Central “finally bought the road,

extending it to Tutwiler on the north and to Belzoni on the south.”(11). This

seems to cancel out Cohen’s report, quoted earlier, on the mythical? Yazoo

Delta R.R. Besides, it was well known in Mississippi around the turn of the

century that although the Y.&M.V. retained a separate name into the 1920s,

it was in fact a part of the I.C. Hence the monopoly scare of 1892 when the I.C.

in the guise of the Yazoo & Mississippi Valley RR. bought out the

Louisville, New Orleans and Texas Railway Company which had become a serious

threat to the I.C. in the Delta. Mississippian industrialists and politicians

saw the $25,000,000 purchase as an extension of the monopoly of Northern

capitalists; in the shape of the Illinois Central. The L.N.O.&T. ran from

Memphis to New Orleans but now as part of the Y.&M.V. In 1938, N .S. Adams referred to the section of the Y.&M.V.R.R. from

Clarksdale to Yazoo City as “the route commonly known as the Yellow

Dog”,(12), but did not state why. In any case, the train would have to jump

the tracks in its efforts to branch from Moorhead to Clarksdale on its arrival

in Tutwiler! (see Fig.3.).

Even if

there had been a Yazoo Delta R.R. which crossed the Southern for only four years

(1899-1903), according to Cohen, it is unlikely that the reference in Charlie

Patton’s “Green River Blues” had the Y.D. in mind. Patton would only have

been about 12 years old when the latter railroad was allegedly swallowed up by

the Y.&M.V. In 1929 he sang the verse Handy had heard in Tutwiler:

“I’m

goin’ where Southern cross the Dog,

I’ni goin’ where the Southern cross the Dog.

I’m goin’ where the Southern cross the Dog.”

(13).

By

this time, the Y.&M.V. had been the only “Dog” crossing the Southern for

some 26 years. Handy of course composed his “Yellow Dog Rag” in 1914 which

later became “The Yellow Dog Blues”. In this form the tune was

recorded by jazz bands and vaudeville-blues singers in the 1920s. In February, 1923, Lizzie Miles cut

what is probably the first recording of the Handy composition, by a blues

singer, as “The Yellow Dog Blues” in New York City. It was to be another two

years or more before Bessie Smith put her most famous version on wax,

accompanied by Fletcher Henderson’s Hot Six. But there does not appear to be

any recordings of Handy’s song by rural blues singers.

By

this time, the Y.&M.V. had been the only “Dog” crossing the Southern for

some 26 years. Handy of course composed his “Yellow Dog Rag” in 1914 which

later became “The Yellow Dog Blues”. In this form the tune was

recorded by jazz bands and vaudeville-blues singers in the 1920s. In February, 1923, Lizzie Miles cut

what is probably the first recording of the Handy composition, by a blues

singer, as “The Yellow Dog Blues” in New York City. It was to be another two

years or more before Bessie Smith put her most famous version on wax,

accompanied by Fletcher Henderson’s Hot Six. But there does not appear to be

any recordings of Handy’s song by rural blues singers.

However,

in 1927 a Louisiana-born singer, who played in McComb, Miss. a great deal, did

record “Yellow Dog Blues” with slide guitar, possibly played across his lap.

This was the manner in which Handy described his guitarist playing in Tutwiler,

and what he heard could well have been the original “Yellow Dog Blues”.

Fig. 3 The Yellow Dog

The

1927 recording, by Sam Collins, (a contemporary of Charlie Patton, Frank Stokes

and Peg Leg Howell), departs

from Handy’s composition and may

well

be the only

recorded evidence of the original blues:

“Be easy

mama, don’t you fade away,

Be easy mama, don’t you fade away.

I’m goin’ where that Southern cross the Yaller Dog.”

“I seed

‘im? here when you was fightin’ all ‘round the hail,

Lord, I seed ‘im here when ‘e? were fightin’ all ‘round the hail.

An’ I felt so rowdy an’ I

didn’t wanna ride no train.”

“I would

ride the Yaller Dog but wary? of Mary Jane,

I wanna ride the Yaller Dog, were wary of Mary Jane.

I dug deep in my saddle, an’ I don’t deny my name.”

“Dug deep

in my saddle, Lord, an’ I don’t deny my name.

Just as sure as the train leaves around the curve.”(14)

I am open to

any suggested alternative transcriptions, especially in the second stanza! Apart

from including the oft-quoted line which inspired W. C. Handy, Collins’ blues

recalls Georgia blues man, Barbecue Bob and his “Easy Rider Don’t You Deny

My Name” recorded the same year, and also the bawdy “Winin’ Boy Blues”

which Jelly Roll Morton was to later immortalize for the Library of Congress.

The various

reasons for calling the Y.&M.V.

line between Yazoo City and Tutwiler, the “Yellow Dog” really need

explanations in themselves! Apart from the rather obvious one about a dog

chasing the train as it passed through Rome, Miss.

(reported by a WPA writer in 1938); I mean some dogs will chase any

moving vehicle.

The story of

how the name was applied to this railroad by the Southern in “friendly

rivalry” has appeared several times but remains mystifying. The sometimes

gangster-ish tactics of the railroad ‘robber barons’ in the 19th. century

are too well known to reiterate here. They were more likely to cut the financial

throat of another railroad in “friendly rivalry”! The chain of flat-cars

hauled by an old locomotive might have some railroad jargon which converts to

“yellow dog” but this remains obscure.

It is

however, a term used by railroad (and others) workers that I believe explains

why they called the Y.&M.V. line the Yellow Dog. This involves an industrial

setting commencing in the 19th. century. The Knights Of Labor “Beginning as a

small society of garment workers in 1869,...evolved into a national organisation

numbering 700,000 members.”(15). Despite much resistance from employers and

communities “the Knights achieved some success, and in 1888 there were thirty

three locals in the state. (Mississippi). But partly as a result of intensified

employer resistance and partly the widespread use by employers of the “yellow

dog” contract as a condition of employment, the Knights lost membership and by

1900 were almost extinct as a national union.”(16). The ‘yellow dog’

contract is explained in a footnote: “The employee is required to sign a card

stating he is not a union member and would not join a union as long as he worked

for the company.”(17). The phrase in its most derogatory form meaning a coward

or in union parlance a “scab”. “...the term “yellow dog” stigmatized

the conduct of the individual willing to be bound by such an agreement.” (18).

Such a

weapon would be only too readily appropriated by other employers including the

railroad companies. In the lumber industry for instance, in 1915 “the Southern

Pine Operators’ Association maintained records of all workers applying for

jobs in the southern lumber companies, and forced the workers to sign away their

right to organize through the acceptance of a “yellow dog” contract”.(19).

Perhaps Moorhead’s founder, Chester H. Pond, used non-Union labour on his

initial section of railroad in the middle 1880s. The Y.&M.V.R.R. might also

have been similarly fixed until the line was ‘merged’ officially into the

accounts or its parent, the almost wholly-unionized Illinois Central, in 1924.

As late as 1925 about 30 miles of the railroad was leased to other smaller

railroads (see 20), which in all probability would have been non-Union.

If one of

these companies had leased some of the Y.&M.V. in 1903 which included

Moorhead and/or Tutwiler, there might have been some derogatory graffiti on the

locomotive such as an abbreviated reference to the yellow dog contract i.e. “Y.D.” This would explain the black section hand’s hesitancy when giving

his explanation for these initials. After all, he would know right away if the

letters stood for the company who was paying him! Some 25 years later, in 1928,

the great blues singer, Lucille Bogan recorded “Payroll Blues” and included

these lines:

“Pay day

on the Southern, pay day on the Yaller Dog,

Pay day on the Southern, pay day on the Yaller Dog.

An’ I want to meet that pay roll an’ try to make a water-haul.”

“Mens out

on the Southern they make dollars by the stack,

Mens out on the Southern they make dollars by the stack.

An’ I have money in my stocking when that payroll train gets back.” (21)

Although

blues lyrics cannot always be taken as autobiographical, it is clear from the

amount of detail that Bogan includes in this and other blues, that she had a

husband/lover who was a railroad employee and probably a fireman, at some stage

in her life. Although based in Birmingham, Ala., Ms. Bogan was originally from

Amory, Miss, in Monroe County and not too far from the Y.&M.V. system. The

payroll train was a phenomenon of the railroads in the earlier part of this

century and travelled many miles, often almost literally stuffed with money,

being the workers’ wages for the last month or more. The implication in the

singer’s lines is that the Southern were far better payers than the “Yazoo

Delta”/Y.&M.V. railroad. If the latter were indeed a non-Union company

they would have usually been paying well below Union rates and hence become the

Yellow Dog.

If indeed the Yazoo Delta R.R. ever existed. Despite a report in 1913 which said that Crenshaw, Miss, in Panola County, was a “new town recently built in the extreme northwestern of the county on the Yazoo Delta railroad,”(22). The Yazoo Delta was a designated geographical area from way back in the 19th. century; when the above report: referred to the only railroad (apart from the I.C.) there was in that part of the Delta, they meant THE Yazoo Delta railroad.

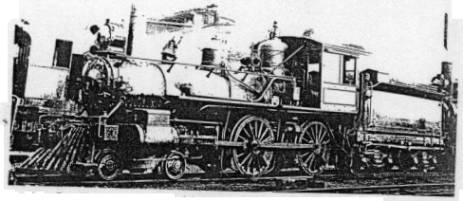

Fig. 4 The Yellow Dog

This became another name for the railroad used by local Mississippians

and was passed on down to the 1950s when blues researcher/author Sam Charters

picked it up and used the phrase “Yazoo Delta railroad” for the caption of

his photo of Moorhead (see Fig.2.). But the company was the Yazoo &

Mississippi Valley Railroad, a subsidiary of the Illinois Central, known widely

in the area by its more popular nickname. Said McIlwaine “So much a part of

living in the Upper Delta was the Yellow Dog, which connected with the Southern

Railway, that black singers made up a song about it...”(23).

An obscure bluesman, Lost John Hunter, even recorded a “Y.M.&V.

Blues” (sic) in the early 1950s in a Chicago style setting with some fine

piano, electric guitar and drums; although he does not include the name

“Yellow Dog”.

The name was

even applied to a locomotive on the Y.&M.V. from the late 1880, which Yazoo

City authorities erroneously referred to as a “train”. (see Fig.4.). But if

it originated with an early form of this railroad, the origin of the term, I

believe, lies in the murky industrial past of the bully-boy tactics of some of

Mississippi’s 19th.(and 20th.) century employers. Nor is my proposed theory

entirely new. In 1954 Frank Smith alluded to the yellow dog contract as a

possible origin for the Y.&M.V. nickname. “One story has to do with the

contract under which the railroad workers were hired.”(24). If this earlier

Delta railroad was a non-Union company, then this would point to the ‘Yellow

dog” contract as being the source of its nickname “The Yellow Dog”

celebrated by blues singers and blacks and whites generally, throughout the

South: before the Second World War. The line in question ran from Yazoo City to

Tutwiler crossing the Southern at Moorhead on the way. The Yazoo &

Mississippi Valley R.R. thus becoming immortalized in the famous blues line

first noted in 1903: “I’m goin’ where the Southern cross the Yellow

Dog.”

Notes

1. Webb W,

Preface.

2. Cohen N.p.442..

3. Ibid.

4. Oliver P.p.67.

5. Wilson J.B.p.p.48-49.

6. Ibid.p.28.

7. Mcllwaine S.p.331.

8. Handy W.C.p.74.

9. Broonzy B.

10. Briegar J.p.L60.

11. Ibid,

12. Adams N.S.p.34.

13. Patton C.

14. Collins S.

15. Mosley D.p.250.

16 Ibid .p .251.

17. Ibid.

18. Adams J.T.p.504.

19. Todes C.p.97.

20. Rowland D.p.558.

21. Bogan L.

22. Riley F.L.p.13.

23. Mcllwaine. Ibid.p.254.

24. Smith F.E.p.p.209-210.

Illustrations

Fig.1 -

DeCell & Prichard.p.353.

Fig.2 – Charters S.p.3.

Fig.3 - Brandfon R.L.p.85.

Fig.4 - DeCell etc. Ibid.p.354.

References

1. Adams James Truslow. (Ed.).

“Dictionary

Of American History Vol.V”. Charles Scribners’ Sons. New York. 1940.

2.

Adams U.S.

“History

Of Yazoo City-Pt.2”. Manuscript in i1ississippi Collection.

University of Mississippi. 1938.

3.

Bogan L.

“Pay Roll

Blues”. Lucille Bogan vo.; Tampa Red gtr.; poss. Georgia Topno. 8 Oct. 1928.

Chicago.

4.

Brandfon Robert L.

“Cotton

Kingdom of the New South”. Harvard University Press. Cambridge, Mass. 1967.

5.

Briegar James.

“Hometown

Mississippi”. Historical & Genealogical Association of Mississippi. 1980.

6.

Broonzy B.

“The

Southern Blues”. “Big Bill” vo.gtr.; prob. A3lack Bob pno.; unk. train,

whistle effect. 26 Feb. 1935. Chicago.

7.

Charters Samuel B.

Notes to

“Rural Blues” (2xL.P.). RB.F. RL2O2. 1964,

8.

Cohen Norm.

“Long

Steel Rail”. University of Illinois Press. Urbana. 1981,

9.

Collins S.

“Yellow

Dog Blues”. Sam Collins vo.gtr. 23 April,1927. Richmond, md. or Chicago.

10.

DeCell Harriet & JoAnne Prichard.

“Yazoo-Its

Legends and Legacies”. Yazoo Delta Press. 1976. Rep. 1977.

11.

Handy W.C.

“Father Of

The Blues”. Sidgwick & Jackson. London. 1957.

12.

Mcllwaine Shields.

“Memphis

Down In Dixie”. The Colonial Press Inc. 1948.

13.

Mosley Donald.

“The Labor Union Movement”. From “A History Of Mississippi Vol.2”. Ed. R.A.McLemore. University & College Press of Mississippi. Jackson. 1973.

14.

Oliver Paul.

“Blues Fell This Morning”. 2nd. Ed. Cambridge University Press. 1990.

I5. Patton

C.

“Green

River Blues,”. Charlie Patton vo. gtr. c. Oct. 1929. Grafton, Wis.

16.

Riley Franklin L. (Ed.).

“Mississippi Historical Society. Vol. XIII”. University of Mississippi. 1913.

17.

Rowland Dunbar.

“History Of Mississippi-The Heart Of The South Vol.11”.

The S. J.

Clarke Publishing Company. Chicago-Jackson. 1925.

18.

Smith Frank E.

“The Yazoo River”. Rinehart & Company Inc. New York. 1954.

19.

Todes Charlotte.

“Labor And Lumber”. International Publishers. New York. 1931.

20.

Webb William.

“The

Southern Railway System-An Illustrated History”. The Boston Mill8 Press.

1986.

21.

Wilson J.B.

“Handbook Of Yazoo County, Miss.” Manuscript in Mississippi Collection. University of Mississippi. 1884.

22. Pre-war

discographical details (unless otherwise stated) from: “Blues & Gospel

Records 1902-1943’. R.M.W.Dixon & J.Godrich. 3rd. Ed. Storyville. 1982.

23.

Correction & addition by Guido van Rijn & Ernest S. Virso Notes to “Lucile Bogan (1923—1935)”.

L.P. blues Document. BD-2046 1989.

24. All transcriptions by Max Haymes. 1993.

Text Copyright © 2002 Max Haymes.

All rights reserved.

Website © Copyright 2000-2008 Alan

White. All Rights Reserved.